Discover Brancusi’s Legacy

The sculpture Traian Vuia

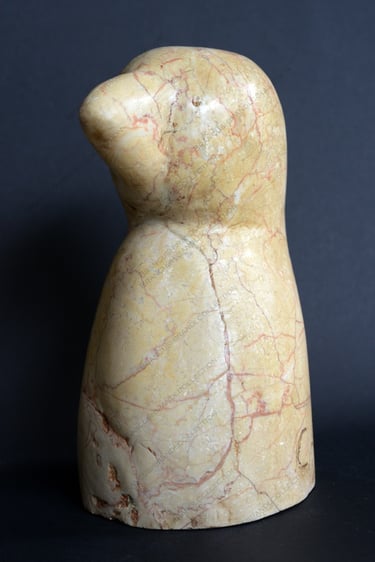

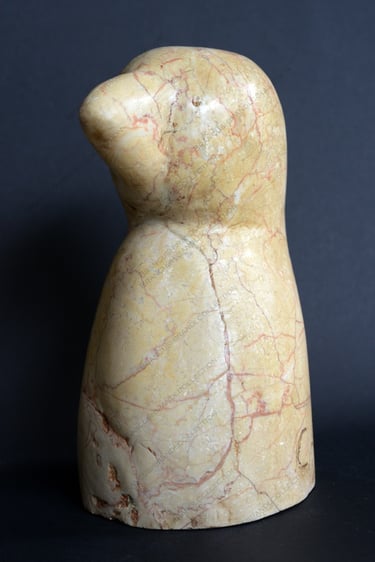

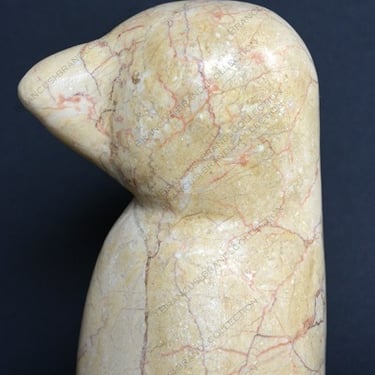

The sculpture Traian Vuia (marble, photos 1–4) is a little-known work by Constantin Brancusi, which we have associated with his series of allegorical portraits. To better understand it, one must first know who Traian Vuia was, his relationship with the sculptor, and then analyze how Brancusi represented him through his artistic means.

10/31/20257 min read

Traian Vuia was a great inventor and a pioneer of world aviation, born on 17 August 1872 in the village of Surducu Mic, Caraș-Severin County, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire; today, the locality bears his name and is included in Timiș County, Romania. Traian Vuia died on 3 September 1950 in Bucharest.

In his memoirs, Vuia recounts that during his childhood in the countryside, and later when he was a student at the Lugoj high school:

“I built kites and tested them in the large field around the camp, at the foot of the vineyards.” [1]

When he finished high school in 1892, Vuia enrolled in evening courses at the Budapest University of Technology, in the applied mechanics section. Financial difficulties forced him to interrupt his studies after one year and to enroll in the Faculty of Law, where he worked in various law offices to support himself. In 1901, he received his doctorate in legal sciences.

Photo 1

Photo 2

Photo 3

Photo 4

Traian Vuia, pioneer of aviation:

The beginnings of the inventor

In the winter of 1901–1902, inspired by the flight of large birds, he developed the project of a flying machine powered by pedals and using air currents. In his own words:

“In my youth, I had the conviction, the belief—indeed the certainty—that I would find the solution to the problem of flight by mechanical means.” [2]

Realizing that he needed additional information in order to pursue his project, he left for Paris in the summer of 1902, where he began to study everything that had been written about flight and about machines capable of lifting off the ground.

On 16 February 1903, Traian Vuia presented before the members of the Paris Academy of Sciences his paper entitled Project for the Aeroplane-Automobile, in which he put forward technical and scientific arguments demonstrating the possibility for a heavier-than-air machine of his own design to lift off and fly. The Commission of the French Academy rejected the paper, considering that:

“The problem of flight with a machine heavier than air cannot be solved and is nothing but a dream.” [3]

On 16 October 1903, he obtained a French inventor’s patent for the Aeroplane-Automobile, and in May 1904 this patent was registered in Great Britain under the title Improved Airplane-Motor. In December 1903, he completed the construction of his aeroplane and began experimental trials.

The meeting with Brancusi

In July 1904, Constantin Brancusi also arrived in Paris, with the same goal: to continue his studies and advance in sculpture.

The two Romanians shared many common points: poverty, the desire to achieve great things, confidence in their own strengths grounded in solid academic training, as well as an innovative spirit.

They also shared a common fascination with flight and engineering abilities, each seeking to realize his dream through his own means: one by building flying machines, the other through the means of art.

They met in 1905 as members of the Circle of Romanian Students in Paris, which included among its members three major figures of world aviation: Traian Vuia, Aurel Vlaicu, and Henri Coandă.

The historic flight at Montesson:

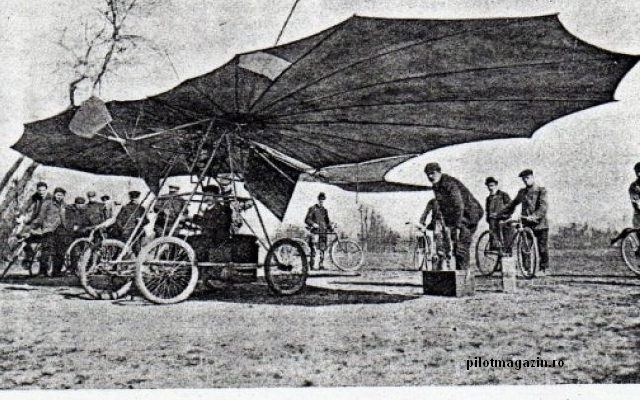

Le 18 mars 1906, à Montesson, près de Paris, eut lieu le vol qui marqua l’histoire de l’aviation : Traian Vuia, avec son appareil Vuia I (photo 5), roula sur environ 50 mètres pour prendre de la vitesse, puis décolla du sol et vola sur une distance de 12 mètres à une hauteur de 0,6 à 1 mètre.

Le moteur s’arrêta brusquement, laissant l’appareil dériver au gré du vent jusqu’à heurter un arbre. Malgré les dégâts, ce fut le premier vol de l’histoire réalisé par un appareil plus lourd que l’air, documenté dans des revues telles que L’Aérophile, La Nature, ou The New York Herald.

Parmi les témoins de cet événement historique se trouvait Brancusi lui-même.

The inventor and the patriot

Vuia did not stop at this achievement. He went on to patent other inventions, including two helicopter models and a steam generator for thermal power plants.

He was also a remarkable political figure and a fervent patriot, campaigning for the union of Transylvania and the Banat with Romania.

In 1946, he became an honorary member of the Romanian Academy, and in 1950 he returned to Romania, where he died the same year.

Today, Timișoara International Airport bears his name.

The connection between Brancusi and Vuia

As a mark of esteem, Brancusi gifted Vuia a Leaf of Life (photo 6), carved from oak wood, a symbol of perseverance and strength for Romanians.

This work is now housed at the Banat Museum in Timișoara, acquired from Vuia’s niece, Cornelia Mateiaș, who stated that she had received it from her uncle in 1947.

Testimonies and memories:

In a conversation reported by writer Dumitru Pascota (1934), Vuia recounted meeting Brancusi in a Parisian restaurant where the artist was pouring water on the tables:

“He is the son of his works,” he said.

The article concluded:

“Two men sacrificed their lives to different ideals, remaining alone, often forgotten, yet living for the same religion: one for the good, the other for the beauty of humanity.” [5]

Another discussion between Vuia and Brancusi, reported by General Ioan I. Stoian, took place in the artist’s studio two days before the Montesson flight. The two Romanians encouraged each other:

Vuia to Brancusi: “It will not be easy for you, because you are poor like me…”

Brancusi to Vuia: “My dear Traian… how did you manage to have the name of a Roman conqueror and another with Dacian resonance? You will succeed in rising above the earth with your flying machine…” [6]

The portrait of Vuia

The writer Victor Eftimiu left a sensitive and precise portrait of the inventor:

“A thin, affable man, full of modesty, yet animated by indomitable energy and impetuous will… He lived poorly and alone, with his only reward being the satisfaction of labor and the pride of a victory whose fruits he did not fully reap.” [7]

Analysis of the sculpture

In Brancusi’s vision, Traian Vuia is a small-scale work (22 cm high, 14 cm in base diameter) yet conveys a striking sense of monumentality. The absence of a pedestal and the slightly widened circular base give the impression of being firmly anchored to the ground, reminiscent of a sphinx.

The artist depicts Vuia as a man-bird, with a prominent nose reminiscent of an airplane’s nose, symbolizing both curiosity and vision. His gaze is directed upwards, and the chest is slightly raised, evoking the image of a resting eagle (photo 7).

Conclusion

Through its simplicity and stylization, this sculpture perfectly conveys Traian Vuia’s inventive and visionary spirit, while also foreshadowing Brancusi’s essential pursuit: capturing the very essence of things.

[1] Vuia, Traian (1954), Realizarea zborului mecanic. Mărturii [The Achievement of Mechanical Flight: Testimonies], Technical Editions, Bucharest, pp. 59–60.

[2] Vuia, Traian (1954), op. cit., p. 59.

[3] Borugă, Elena (1999), Traian Vuia 1872–1950 – Studiu monografic și catalog [Traian Vuia 1872–1950: Monographic Study and Catalogue], Mirton Editions, Timişoara, p. 14.

[4] Borugă, Elena (1999), op. cit., p. 77.

[5] Pascotă, Dumitru (1934), Vuia şi Brâncuşi [Vuia and Brancusi], Vestul, Timişoara, April 26.

[6] Stoian, Ioan I., retired Air Fleet General (2010), Traian Vuia şi Constantin Brâncuşi, genii ale neamului românesc [Traian Vuia and Constantin Brancusi, Geniuses of the Romanian People], Vestea, Mehadia, January 2.

[7] Eftimiu, Victor (1965), Traian Vuia, in Portrete şi amintiri [Portraits and Memories], Editions for Literature, Bucharest, pp. 446–447.

Bibliography

Photo 5

Photo 6

From the front, the sculpture can be framed within a trapezoidal geometric shape (photo 1). The head is slightly separated from the body by a shallow recessed area, while the rest of the body is enveloped in a cloak. For the artist, the form of the body itself is of little importance; what matters are the posture and the elements that define it. This enveloping cloak can be seen as influenced by Rodin’s Monument to Balzac (1897).

The dorsal part can be framed within a cylindrical geometric shape, with the head exaggerated in size, occupying roughly half the height of the body (photo 2), indicating its significant importance for the sculpture.

In profile, the sculpture reveals the straight line of the back, corresponding to the spine (photos 3 and 4). From this angle, the sculpture can also be framed within a trapezoidal geometric shape.

Photos 8a and 8b show the lateral and frontal views of the man-bird’s nose, which strikingly resembles the “nose” of modern airplanes (photos 9a and 9b), demonstrating Brancusi’s technical foresight and vision.

Photo 7

Photo 8 a

Photo 8 b

Photo 9 a

Photo 9 b

The sculpture, carved in white marble, has a warm pinkish-brown patina and retains traces of a light red ochre paint—a type of clay historically used as a pigment. This technique, influenced by ancient statues where marble was often painted, was employed by Brancusi during his early period; he later abandoned it as he became increasingly focused on the inherent structure of materials.

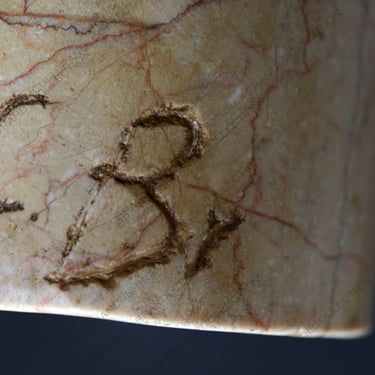

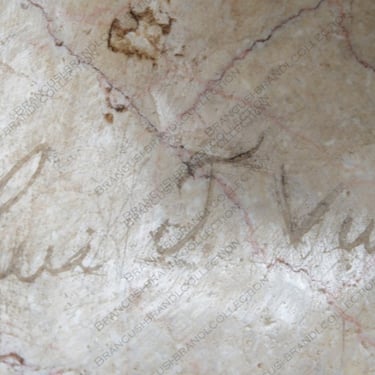

The sculpture is signed on the lower left side with an incision, “C. Br,” consistent with Brancusi’s signature style at the time (photo 10a). On the base, calligraphic letters inscribe the dedication Lui T. Vuia [To T. Vuia] (photos 10b, 10c).

Photo 10 a

Photo 10 b

Photo 10 c

Other articles you may like

Contact

For any questions, contact us here.

Follow us

Subscribe

© 2025. All Rights Reserved.