Discover Brancusi’s Legacy

Analysis of the Jesus Christ Sculpture Series

Constantin Brancusi spent his formative years (1894–1898) at the School of Arts and Crafts in Craiova under difficult circumstances. Orphaned and forced to work in order to support his family, he nevertheless forged the foundations of his future success. Sustained by his faith, relentless work ethic, and precocious talent, he devoted himself to sculpture, modeling, and the local spiritual life. These formative years shaped both the man and the artist he would later become.

11/16/20257 min read

Between 1894 and 1898, Constantin Brancusi attended the School of Arts and Crafts in Craiova. These were difficult years for him: still an adolescent, orphaned of his father, living far from home, he had to work tirelessly to support himself while also helping his family in Hobița. He was sustained by determination, intelligence, practical skills, and above all by faith, which was his greatest strength—it enabled him to overcome hardship and ultimately succeed in life.

The years spent in Craiova laid the foundations of his later success, as he would acknowledge to close friends in later years. At the School of Arts and Crafts, he acquired everything he needed to become a respected sculptor and learned how to make the most of the spark of genius with which he had been endowed at birth. He relied on two fundamental pillars: faith and work.

He rose early in the morning and worked until late at night. The little free time he had was devoted to exploring the city and to modeling, sculpting, and chiseling decorative, artistic, and domestic objects, which he then offered with great affection to his friends and benefactors.

He regularly attended the city’s churches and maintained close relationships with priests. He prayed for his own well-being and that of his family, as he had seen practiced at home, where his mother, brothers, and sister attended the services at the Tismana Monastery. In the churches, Brancusi took an active part in religious services, helped with maintenance work, sang in the choir, and made various donations in the form of devotional objects he had crafted himself, as documented in records from that period.

Introduction

Presentation of the Sculptures on the Theme of Jesus Christ

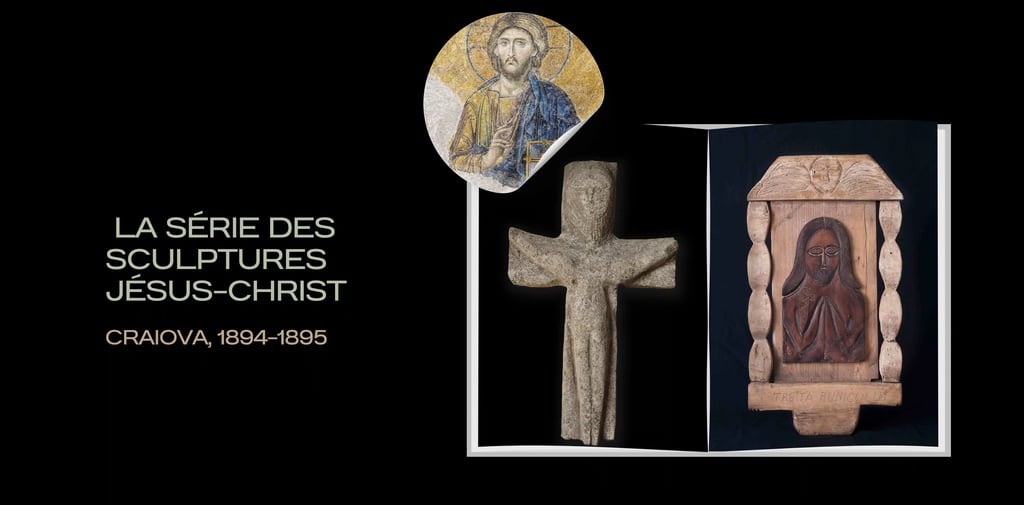

From the years Constantin Brancusi spent at the School of Arts and Crafts, three sculptures on the theme of Jesus Christ have survived. Created outside the school curriculum, they belong to a series of religiously themed works characteristic of his Romanian period, which he would leave behind after departing the country in 1904. This limited series consists of The Head of Jesus Christ, The Trinity of the Grandfather, and The Crucifix.

The materials used for these three sculptures are terracotta, wood, and stone— inexpensive materials, easy to obtain and to work with, and requiring no special tools. These were the materials commonly used by the peasants of Oltenia for construction and decoration, as well as for the making of household objects.

In The Head of Jesus Christ and The Crucifix, Brancusi introduced certain elements specific to the Catholic Church, such as the two-dimensional and three-dimensional rendering of the body. In the Orthodox Church, the body of Jesus Christ is painted rather than sculpted. This Western influence can be attributed to the Austrian masters at the School of Arts and Crafts, with whom Brancusi was close, as well as to the small Austrian and Italian community established in Craiova, which he frequented. At the time, he was employed as a shop assistant by Ion Zamfirescu, a prominent merchant who owned a colonial goods and confectionery store.

In a society marked by an excessive and almost closed conservatism, creating a modeled terracotta head of Jesus Christ and a stone crucifix represented both an innovation and an act of great artistic courage on the part of a future artist free of inhibitions and open to the renewal of Romanian art. The fact that these sculptures were accepted, and that Brancusi was not ostracized, was due to the respect he enjoyed among the elite of Craiova after crafting a violin with a pleasing sound, made from the wood of an orange crate.

Fig. 1a – The Head of Jesus Christ by Brancusi (terracotta, ca. 1894)

Fig. 1b – Pietà by Michelangelo (terracotta, 1498–1499; source: Michelangelo e la Pietà in terracotta. Studi e documenti / interventi / diagnostica, Erreciemme Edizioni, 2019)

Fig. 1a

Fig. 1b

The Head of Jesus Christ

The sculpture The Head of Jesus Christ is executed in terracotta, in the round, measuring 40 × 30 cm. It is neither signed nor dated (Fig. 1a). The facial features are finely crafted and harmonious, conveying an overwhelming tragedy—one might even say a metaphysical one—which allows it to rival the Head of Jesus Christ from Michelangelo’s Pietà (Fig. 1b).

The sculpture The Trinity of the Grandfather (Fig. 2a) belongs to the broad family of devotional monuments in Romania which, until the beginning of the 20th century, replaced churches when poverty and wars made the construction or use of proper places of worship impossible. The Trinity of the Grandfather consists of the bust of Jesus Christ executed in terracotta and fixed with screws onto a wooden board; on the front face of the base, the designation Trinity of the Grandfather is stamped, indicating that the work was created in his honor.

The work measures 62 × 35 × 4.5 cm. It is not dated, but is signed “CB” on the left hand of Jesus Christ, near the wrist. It is decorated only on the frontal side, where the face of Jesus Christ displays the characteristics of Byzantine icons (Fig. 2b): enlarged eyes, a small mouth, a straight and slender nose, and hair and beard arranged in slightly wavy locks.

On the lateral sides, on either side of the Savior, there are two pillars composed of four pulsating elements, representing energy channels that connect heaven and earth, through which energetic communication takes place between humankind and the Divine. At the top, the roof is crowned by a seraph, executed using the technique of contour carving.

On the figure of Jesus Christ, one can observe the presence of two pairs of simplified hands shaped like propeller blades—means that facilitate the circulation of energy and matter. These can be interpreted as follows: the first pair of hands represents those of Christians in prayer, the foundation of Orthodoxy; the second pair represents those of the Savior, who receives the energy of the prayers and transmits it onward to God the Father through the seraphim, the guardians of paradise and sacred places.

On the right shoulder, toward the chest, there is the outline of a cross, a sign of bearing the cross on the shoulder on the way to the place of crucifixion.

The Trinity of the Grandfather

Fig. 2a

Fig. 2b

Fig. 2a – The Trinity of the Grandfather by Brancusi (terracotta and wood, ca. 1894)

Fig. 2b – Jesus Christ Pantocrator, mosaic fragment from Hagia Sophia, Constantinople

This Trinity is the first work in which Brancusi employs plastic metaphor, motif, and symbol rendered through artistic means; in essence, the work constitutes a synthesis of Orthodox faith. Here and now, the young sculptor introduces into his creation a personal code—the Brancusi code.

Crucifix

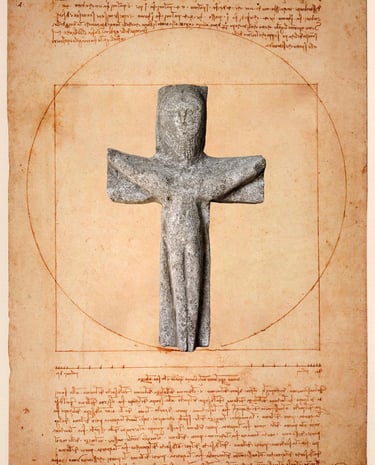

The third work in the series is the Crucifix, executed in stone in high relief (Fig. 3a), measuring 43 × 25.5 × 7 cm. The back is inscribed (incised) with the signature, location, and date: “C. Br CRAIOVA 1895” (Fig. 3b).

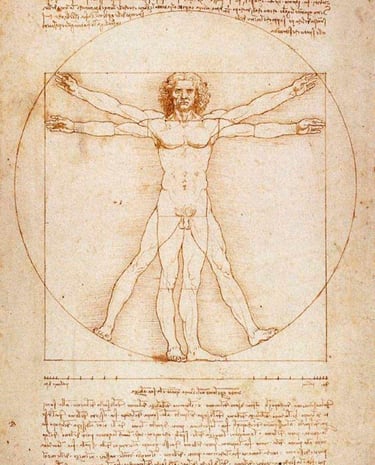

This crucifix demonstrates Brancusi’s sublimation of the forms of Jesus Christ and the monumental quality of the sculpture. The crucified Christ in Brancusi’s vision mentally evokes Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, also known as the Canon of Proportions or less commonly Proportions of Man (1492, Fig. 3c). Comparing Leonardo’s drawing, considered the representation of the ideal male body, with Brancusi’s sculpture (Fig. 3d), one can see that he also sought to establish an optimal relationship among the body’s dimensions, according to the knowledge he possessed at the time. Monumentality would later become a central goal in his mature sculpture, which he defined as derived from the proportional relationships within a work rather than from its actual physical size.

Fig. 3a

Fig. 3b

Fig. 3c

Fig. 3d

Fig. 3a – Crucifix by Brancusi (stone, 1895) – front view

Fig. 3c – Vitruvian Man by Leonardo da Vinci (drawing, 1492; source: reproduction of the original, Museo Nazionale Scienza e Tecnologia Leonardo da Vinci, Milan)

Fig. 3d – Comparison of Brancusi’s sculpture proportions with da Vinci’s drawing

Brancusi’s Crucifix is a typical representation of the Catholic Church, into which the sculptor incorporates certain elements characteristic of Byzantine icons: enlarged eyes, a small mouth, a straight and slender nose, and hair and beard depicted in slightly wavy locks.

Conclusions

The analysis of Constantin Brancusi’s Jesus Christ series, created in Craiova in 1894–1895 while he was a student at the School of Arts and Crafts, highlights the three sculptures composing the series: The Head of Jesus Christ (terracotta), The Trinity of the Grandfather (terracotta and wood), and the Crucifix (stone). These works are framed as devotional objects aligned with both the Catholic and Orthodox traditions, executed through modeling, contour carving, and high relief sculpture.

Brancusi’s innovations in this series include the introduction of elements specific to Byzantine icons into Catholic devotional objects and the use of artistic means to convey plastic metaphors, motifs, and symbols—elements that would later form his personal artistic code.

The materials Brancusi employed for these three works were among the most common in Oltenian peasant households, used for construction, decoration, and the making of domestic objects.

The Head of Jesus Christ and the Crucifix recall works of the universal artistic heritage—Michelangelo’s Pietà and Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man—which Brancusi may not have known, suggesting that great artists worldwide share a common source of inspiration: divinity.

These three works demonstrate that Brancusi’s formative point in artistic creation was the School of Arts and Crafts in Craiova. The techniques, artistic elements, and themes he employed underwent profound transformations during his later studies at the Bucharest School of Fine Arts and took a dramatic leap forward after he settled in Paris. Brancusi referred to this evolutionary significance in art as “rubbing the diamond.”

Selected Bibliography

Doina Frumușelu (2013), Brancusi: The Beginner, RCR Editorial, Bucharest, ISBN 978-606-8300-19-1.

Doina Frumușelu (2014), Brancusi: Testimonies, RCR Editorial, Bucharest, ISBN 978-606-8300-58-0.

Doina Frumușelu (2015), Brancusi: A Life Between Two Centuries, RCR Editorial, Bucharest, ISBN 978-606-8300-85-6.

Doina Frumușelu (2017), Brancusi: Seen by His Contemporaries and Commented on by Posterity – PhD thesis in Visual Arts, George Enescu National University of Arts, Iași, ISBN 978-973-0-24062-7.

Fig. 3b – Crucifix by Brancusi (stone, 1895) – back view

Other articles you may like

Contact

For any questions, contact us here.

Follow us

Subscribe

© 2025. All Rights Reserved.